Are Librarians Information Architects?

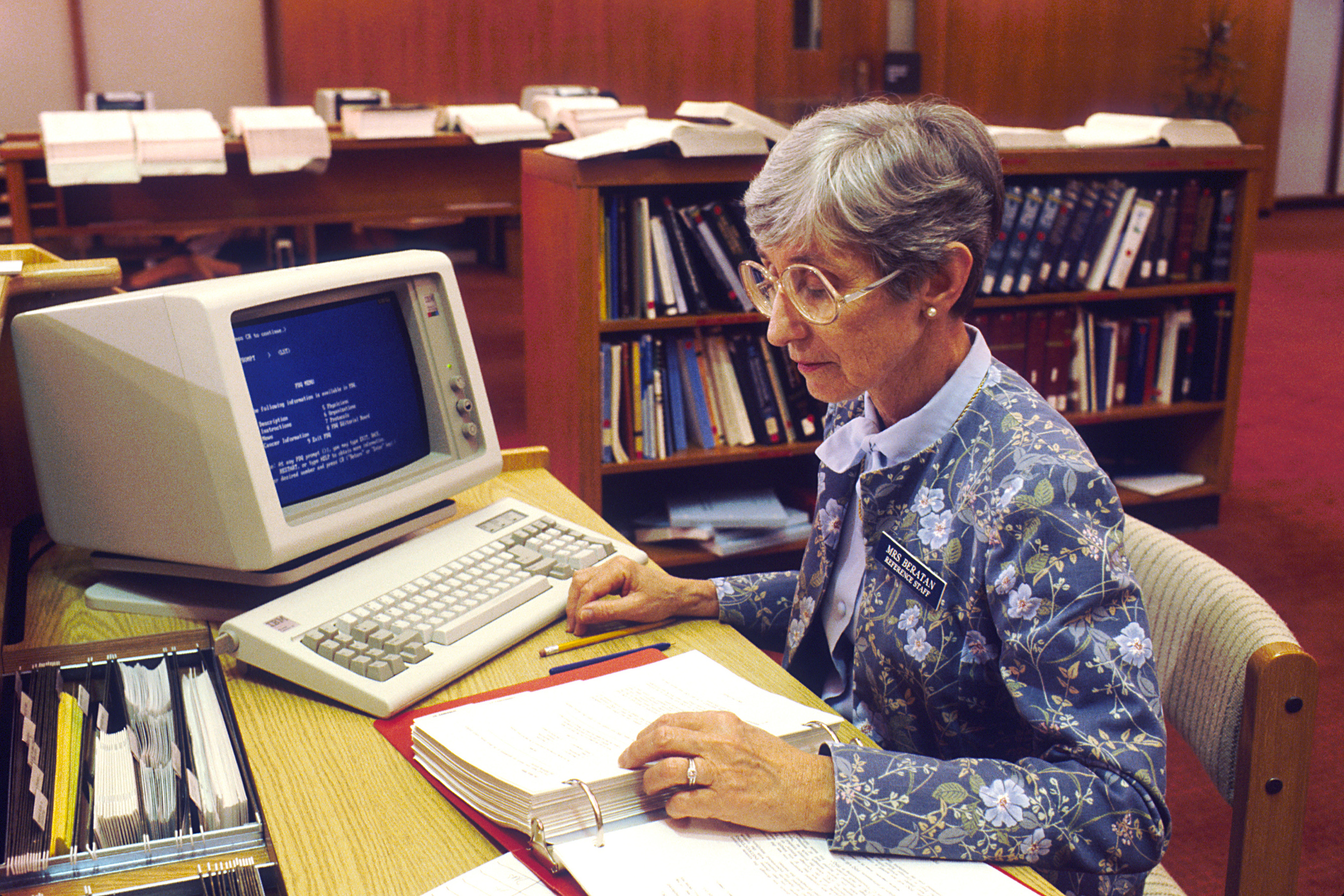

An old woman putting an index finger to her mouth and saying, “Shhh!” Most likely wearing a pair of glasses with a little metal chain—the same chain banks use to ensure its patrons don’t walk away with the pen they use to fill out a deposit slip. For better or worse, this is the first image that comes to my mind when I think of a librarian.

But librarians aren’t crotchety old ladies. They’re actually information guardians. Simply put, librarians help library patrons find and access information in a wide variety of formats.

Information architecture is a discipline that emphasizes organizing and presenting information in a way that ensures optimum findability and usability across different media devices and channels.

Let’s continue with that word “findability.” The main similarity between the role of a librarian and the function of good information architecture is an emphasis on findability. Librarians create and implement organizational schemes such as the Dewey Decimal System so library patrons can easily find what he or she is looking for, whether it’s a periodical, a textbook, a movie, or an article. Information architects make sure information on a platform is easily found and understood by its users, whether that user is on a smartphone, computer, tablet, or other digital device. According to Rosenfeld, Morville and Arango: “If users can’t find what they need through some combination of browsing, searching, and asking, than the system fails.”

Whether it’s a library or a mobile app, whether you’re a librarian or an information architect, the stakes are the same—if your user can’t find the information he or she is looking for, you stink at your job.

The other obvious similarity between librarians and information architecture is the need for both to adapt to a rapidly changing technological landscape. Over the past two decades, old paper card catalogs have been replaced with online search databases, and ebooks have joined paperbacks and hardcovers under the same roof. As we see in the example of Mario, the rise of portable digital devices has given way to many different methods of consuming and interacting with media. Both disciplines need to adapt and deal with the digital revolution head-on.

Meredith Schwartz’s description of the modern librarian in Library Journal could easily apply to an information architect: “Today’s libraries are full of collegial, and sometimes even downright noisy, collaboration, creation, and community activities, and are as much about technology as print on paper. Modern librarians need to be comfortable and conversant with technology, be willing and able to speak in public, and possess people skills and a commitment to lifelong learning, as the profession and the expertise necessary for success are constantly changing.”

However, this is where the similarities end. The main difference between information architecture and library science is the emphasis on users and devices; in order for information architecture to succeed, the designer absolutely must take into account the users and the way they consume information.

In our textbook, the authors write: “Underlying this model is a recognition that you can’t design useful information architectures in a vacuum. An architect can’t huddle in a dark room with a bunch of content, organize it, and emerge with a grand solution.” I would argue that the Dewey Decimal System is the result of organizing information in a vacuum—books are organized to ensure maximum findability for anyone who happens to walk into the library seeking information. Of course, librarians do take users into consideration, but they’re not in the trenches like information architects are when it comes to creating organization schemes.

Information architects need to take into account content, context and users. And, according to Rosenfeld, Morville and Arango, all three are moving targets: “Users can vary in their attitude, demographics, psychographics, tasks and information needs, information-seeking behaviors, and more.”

And why does information architecture place a premium on understanding its users? Because there are more ways to access information than ever before. As we see with the example of Mario, people nowadays are basically walking around with miniature libraries in their pockets, from the music collection on their iPhones all the way to the ebook inventory on their Kindles. Mario is almost his own librarian, looking to organize and access information in the easiest way possible across multiple devices that are constantly improving and changing: “This is not the old world of yellowing cards in a library card catalog. We’re talking complex, adaptive systems with emergent qualities. We’re talking rich streams of information flowing within and beyond the borders of departments, business units, institutions, and countries.”

The digital revolution has also led to the “dematerialization of information.” Content in a textbook is no longer tied to its spine and music housed on a compact disc is no longer stuck on a piece of plastic. While librarians are tied to organizing information according to artifact—a textbook, DVD, compact disc, audiobook—information architects must confront this decoupling of information from its artifacts head-on. Good information architecture works across multiple channels and doesn’t confuse its users as they switch from computer to tablet to phone to the interactive dashboard of their car.

Resources:

Rosenfeld, Louis, Peter Morville, and Jorge Arango. Information Architecture For the Web and Beyond. Sebastopol, CA: O’Reilly Media, Inc., 2015. Print.

Schwartz, Meredith. "How To Become a 21st Century Librarian." Library Journal. Library Journal, 20 Mar. 2013. Web. 30 May 2016.